Old Galway

SCOIL ÍDE, SEVENTY YEARS A-GROWING

by Tom Kenny

On this day seventy years ago, June 1st 1953, Scoil Íde opened for the first time. In 1952, the Sisters of Jesus and Mary purchased Allen’s Hotel on Dalysfort Road which had been run by John and Angela Allen. It had at one time been known as Daly’s Fort House, a high-class hotel run by a Mrs. Galbraith. She sold it to a Mr. Miller of Persse’s Distillers who used it as a private house and he sold it on to the Allens. Many will remember it as the place where Bruce Woodcock, the English Heavyweight champion, trained for his famous fight with Máirtín Thornton.

The Sisters converted the building into a school. Two of their congregation, Mother Mary Immaculata and Sister Celine, were given the job of setting it up. They lived in Spires House in Shantalla and every morning, Professor McKenna would give them a lift to Taylors Hill and they would walk from there, across the fields to the school where they were joined by teacher Miss Celia Burke.

TOMÁS BÁN AND HELENA CONCANNON

by Tom Kenny

Tomás Bán and his wife Helena were two people who made an outstanding contribution to the cultural enrichment of Galway and indeed of the country generally in the first half of the last century.

Tomás Bán was born on Inis Meáin on November 16th, 1870, the son of Páidín Concannon and his wife Annie Faherty. He was educated on the island and unusually for an islander, in the Monastery School in Galway. As a teenager, he was taken to the U.S. where he graduated with a MA in accountancy. He worked for a while in his brother’s vineyard in California, started a business in Mexico and it was there that he first began reading in the Irish language. He came back to Ireland in 1898 for a holiday but he became so immersed in the workings of the Gaelic League that he stayed and became their first ever organiser travelling the country at his own expense until they started paying him. He toured the U.S. in 1905 with Douglas Hyde on behalf of the League and they collected £20,000 for the cause. Tomás Bán worked in Monaghan until 1912 when he became a health inspector in Galway.

OF POSTMEN AND POSTWOMEN

by Tom Kenny

The regular use of the words ‘litir’ and ‘post’ in 15th century Irish manuscripts suggests that by that time a postal system was already in existence in Ireland. The English postal system was completely reformed by a man named Witherings in 1638 and he was then invited to do the same in Ireland. By the 1650s, mail was being carried by post boys who walked 16 – 18 miles a day between towns. It is believed the Galway Post Office was set up in 1653 when the Cromwellians were still here. In those early years, the local postmaster was expected to provide the premises, so every time a new postmaster was appointed, it meant a new main Post Office.

Most official Post Office archives were destroyed in the GPO during the 1916 Rising so early postal records are scarce. In 1663, the posts increased from once a week to twice a week on the three post roads from Dublin, the Cork Road, the Ulster Road and the Connaught Road but it could be dangerous driving the mail van. Some years ago, in this column, we reproduced a poster from 1837 offering a reward of five guineas for the recovery of mail bags lost on Christmas Eve between Galway and Tuam. For much of the 19th century, the mail coaches needed to be accompanied by two armed guards to discourage robberies.

“IT WAS IN THE AIR”

by Tom Kenny

Prior to 1961, public performance of Irish Traditional music in Galway took place primarily in the form of Céilís in large dancehalls – namely in the Hangar, the Commercial and the Astaire. These were enormously popular – remember the hundreds of bicycles parked outside the Hangar on a Sunday night – but they began to go out of fashion in the sixties and were regarded as old fashioned and backward.

Singing and music in pubs was generally frowned on and if you sang, you were likely to be thrown out. There were two exceptions to this, Cullen’s Bar in Forster Street and the Eagle Bar at the corner of William Street West and Henry Street. The owners, Martin Forde and Larry Cullen had an affinity with traditional music and musicians, but the sessions were intermittent and semi-private. In the Eagle, the recently formed (1956) branch of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí met and the Loch Lurgan Céilí Band used to rehearse.

The Jesuits in Galway

by Tom Kenny

There is historical evidence to show that the Jesuits were already in the city in the early 1600s, combining the work of ministry and education. In 1645, the Order set up their first college in Galway on Lower Abbeygate Street, where Powell’s shop is today. They were forced to leave the city by the Cromwellians, but they came back. They were forced to leave the city by the Williamites, but they came back. They had to close their Galway residence in 1768 due to a lack of manpower but they were persistent and came back again, and in 1859 they took over a house on Prospect Hill and the following year, set up a college in Eyre Square.

They then bought a site on Sherwood Fields on Sea Road, and in March 1861 they laid the foundation stone for a new college and residence there. Eleven months later, the building was sufficiently finished for them to move in and begin teaching classes. In March 1862, work began on the building of the church.

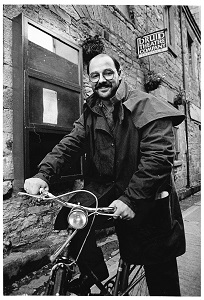

Maelíosa: A MAN OF MANY PARTS

by Tom Kenny

Maelíosa Stafford did not really have a chance, he was destined for a life in theatre, drama was in his blood, acting in his DNA. His first time on stage was in a Taidhbhearc production his mother was acting in … he was still in his mother’s womb. Both of his parents, Seán and Máire had made an enormous contribution to the arts scene in Galway and especially to theatre in the west, in various guises as actors, directors, translators of plays into Irish, writers of pantomimes, costume designers, librettists, drama teachers.

There was many a time Maelíosa had to be minded in the green room while his parents were on stage in An Taidhbhearc. His mother and father used to organise a theatre school for children in the Árus in Dominick Street where they taught elocution and stagecraft. They would rehearse and perform little sketches and plays there and occasionally in Feiseanna and always As Gaeilge. Our first photograph shows Maelíosa, complete with moustache and turban, in one of those productions, aged about four.

SCOIL FHURSA, NÓCHA BLIAIN AG FÁS

by Tom Kenny

The Irish Church Missions was the missionary wing of the Church of Ireland & England. They were a very rich organisation who felt it was imperative to convert Roman Catholics “from the errors of Popery”. Around the year 1850, they had two houses in Merchant’s Road and established a school in one of them (known as The Dover School) where a child might get an evening meal and a night’s lodging after attending a bible class.

They felt a new Mission Schoolhouse and dormitory was needed, so in 1862, they built it at Nile Lodge and it became known as “The Sherwood Fields Orphanage”. The building, which was much smaller then, was of cut stone and consisted of a church and a classroom facing south with a dwelling house in the centre. Behind was the refectory. Some of the floors were paved with cobble stones. Like most ‘Bird’s Nest’ schools it was a boarding school and housed mainly Conamara children. Because of the proselytising, the Catholic clergy and most of the population were against the school. The food consisted mostly of Indian meal and brochán, a kind of soup that lead to the term ‘Soupers’.

AIDAN HEFFERNAN, A SPORTING CHAMPION

by Tom Kenny

Aidan was one of thirteen children born to John and Lena Heffernan who lived in 143, Bohermore. John was originally from Lower Salthill and worked in the ESB. Aiden went to school in St. Patrick’s and later to Moneenageesha.

His older brother Michael John became a champion boxer, so it was only natural for Aidan to follow in his footsteps. When he was eleven years old, he joined St. Patrick’s Boxing club and he trained with them in the Community Centre which was close to the terraces in Bohermore. It was a very lively and active club overseen by people like Fr. Seán Foy, Mickey Fitzgerald and Pa Curran. The boxing coach was Seán Harty, himself a former champion, and he excelled at training and encouraging the young hopefuls.